Guillermo Gómez Peña’s Live in America Cocktail

What ensues is our sneaking across a dark lawn, crouching between trucks. There is some minor trespassing, some sneaking onto a porch, some unproductive peeping action. Multiple times, I bring up guns and the fact that we’re in Arkansas.

Time:

How long do you want to be hungover?

Ingredients:

Diet Coke

Kombucha

Fireball

Ice

Red solo cup

If you want to zhuzh:

Bitters

Lime wedges

Step One: Consider Your Setting

Think about a great cocktail bar. Think about all its smoothly curved stainless steel tools, all the beautiful liquor bottles, the leather stools, the glitzy patrons, the repressed longings, all the craft booze-pouring/shaking that just flourishes inside. Now take all of that away. That’s not the where and how of this cocktail recipe. Instead picture a cute craftsman home whose full-time resident artists are drinking less, and so they don’t have much liquor around. There’s a cooler of coke and diet coke and sparkle waters as well as a cooler of Modelo. But no bitters, no tequila, no back-lit bottles of gin. However, because these two artists remain cocktail fans, there are tools– a stainless steel shaker and a jigger, plenty of ice. But alas no mixologist and no actual booze.

But glittery patrons? Oh, we have those. And I would venture to say on this particular birth-of-a-heretofore-unknown-cocktail night, we host enough glittery artists with enough longing to explore and to adventure, to wander across the lawn to in order to peep through the eccentric neighbor’s window, that their inevitable shenanigans rival those of any late night bar crowd. But despite this gathering of glitz and glam and longing and well frankly, mania, our celebration is initially missing the creative spark that will move the night’s festivities to the next level.

Step Two: Gather Your Sparks

Think of this as a found cocktail. Ie, someone found all these ingredients and then mixed them together to make a cocktail. The first spark/ingredient, Fireball, arrives with a local city council person. At the door, they present to the hosts a literal bucket of premeasured Fireball shots and some holiday-flavored Chapstick. We immediately do shots of Fireball. I say to myself, “Mistake number one tonight.” The bucket of Fireball lives on the dining table, and all night, as new guests arrive, they remark, ”My god, is that a bucket of Fireball shots?” Yes, yes it is. (By the end of the night, it will be empty.) But initially, the Fireball remains untouched until the arrival of a certain performance artist of note, ie spark two.

When Guillermo Gómez Peña walks in with his artistic and life partner, Balitrónica, I am a bit starstruck (well, way more than a bit). Starstruck as only someone who has a PhD in obscure performance practice can be in the presence of Guillermo Gómez Peña. Guillermo is a Mexicano/Chicano performance artist/activist/writer. I studied him throughout my doctoral program. In those days, he was fascinating to me because he was one of the few Mexicano/Chicano performers with whom academic-y, art-fancy people were fascinated, and yet he managed to achieve the status of “fascinating” without having to center his career around white narrative structures.

Like for so many other scholars/artists, Gómez Peña’s performances in museums captured my imagination. My favorite was a collaboration. In the early 90s, in partnership with Coco Fusco, the two famously staged The Couple in the Cage: Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West. This performance lives so hard in my brain that I can describe it to you now without looking at a reference. In this work, first performed to mark the anniversary of Columbus’s “discovery” of America, Gómez Peña and Fusco outfitted themselves in quasi-authentico Native American drag. Their museum performance space was marked with traditional institutional trappings: encyclopedia-style articles and museum plaques, all with museum-quality writing. All very officious. In the museum, they inhabited a literal cage chock full of stereotypical Native paraphernalia and chock full of signs of the West, including Coke bottles and laptops and a Polaroid camera.

With their performance of a fictional pair of undiscovered Native islanders trapped in a cage, they unleashed the assumptions and stereotyping and racismo of the audience. Despite the telltale signs of irony, many museum-goers treated Fusco and Gómez Peña as objects, as animals, as other: asking to see Fusco’s breasts, harassing the performers with ape sounds and rattling their cage, handing them bottles filled with piss, generally accepting the whole ironic fiction as fact. The audience remained privilegedly unaware of the social/historical critique they themselves created with their performative responses to The Couple in the Cage.

With photos from the performance slide-showing in my mind, I watch Gómez Peña from across the room. Shorter than I imagined. Good rings. He leads with a discussion of how many brujas he senses in the house. He exhibits a deep appreciation for good beans. Offers a dick joke. In a short time, he is unapologetically holding court around our dining table. And of course, he wants a cocktail. And of course, the only liquor we have is that bucketful of Fireball shots.

Step Three: The Shake

Making do with items on hand, Guillermo gamely mixes over ice in a shaker equal parts Fireball, Kombucha, and Diet Coke. He serves this concoction with ice in a red plastic igloo cup. (And when I tell him that I am going to write about this concoction, he requests that I underscore that the ice is essential. He also tells me to tell you that if he ever tries the mix again, he’ll experiment with bitters and some lime wedges.)

Anyway, Guillermo and I are introduced. He immediately hands me a cup of his new cocktail. I am surprised and overwhelmed, more by his presence than the drink. I try to focus, keep my fangirl shit together. I take a sip. Oddly thirst-quenching. But as this mix of dieted godforsaken chemicals, spicy cinnamon, and vinegar water race through my body, it unleashes the floodgates, and I start to gush to Guillermo. What his work means to me, appreciation for how he carved out room in practice and in institutions for someone like me to imagine her own arts practice. I choke up. I also choke on the drink. Faced with tears and gagging, Guillermo is gracious. I am sure many have gushed-choked at him before. But the party keeps moving, and not wanting to appear like a total stalker, I drift away. The next time we connect, he comes to me with a question.

His question goes something like this: I have heard next door there is a performance artist última. She lives her everyday life inside performance. Can you come outside and tell me more, maybe show her to me? Now, it is true that our neighbor only wears period clothing. She’s a costume designer and a historian, and she is so dedicated to her craft that she sews her clothes with (and in terms of the earliest cases without) period-appropriate machinery. And it is true that this is a lifestyle choice in that she and her kids only ever wear these historical clothes and refer to their modern clothes as “pajamas.” And it is also true that watching someone dressed like Martha Washington step out of an SUV while holding a Big Gulp is quite a performative experience. But nonetheless, our neighbor does not refer to herself as a performance artist. I explain all these circumstances to Guillermo along with the neighbor’s fascination with the decorative macabre. His response: I must see for myself.

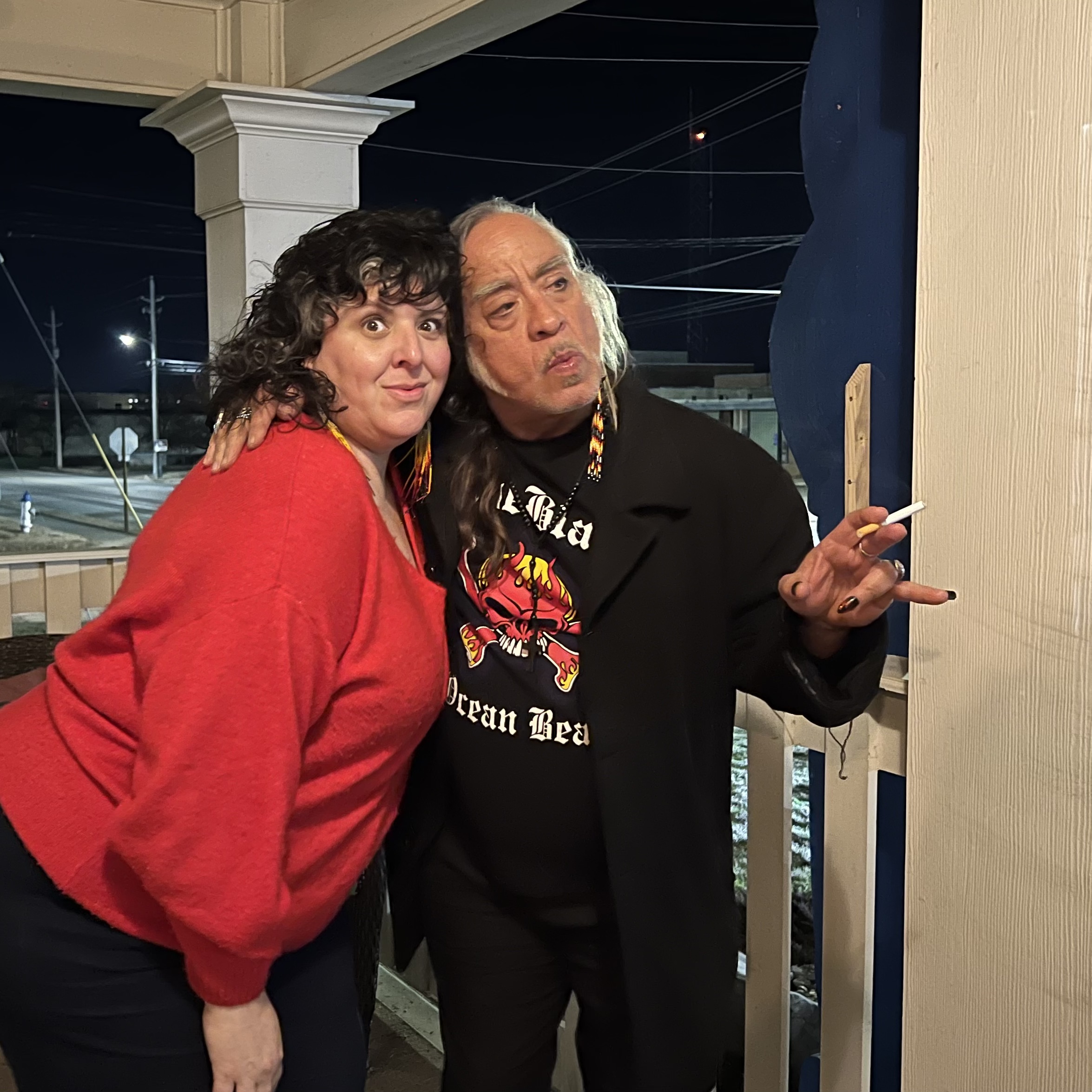

What ensues is our sneaking across a dark lawn, crouching between trucks. There is some minor trespassing, some sneaking onto a porch, some unproductive peeping action. Multiple times, I bring up guns and the fact that we’re in Arkansas. I explain “defend your ground.” And eventually the message gets through. As we cross back over the neighbor’s lawn, Guillermo removes his cigarette to cough. He looks at me and says that he only answers to two gods: American Spirits and Albuterol. Then we take selfies on the porch.

Step Four: Offsetting Dark Magics

I have several of Guillermo’s cocktails. Several more than several. But here’s the true miracle. I don’t puke. I don’t get a headache. I never remotely skirt morose-alcohol-fueled-sadness. And I should have. I should have been very sick and probably crying at 3am. The only conclusion I can draw is that somehow the Kombucha mixed with a lot of borracho beans and stirred with the force that is Guillermo Gómez Peña healed me, offsetting all the dark magics.